The New Information Layer: Why Political Organizations Must Own Their AI Visibility

Political communication is colliding with a new information layer. Voters now ask ChatGPT, Gemini or Google’s AI Mode to explain what parties stand for, who seems credible and how policy trade offs compare, often before they see a single ad or click a result. Google reports that more than 1.5 billion people have used its AI generated summaries, and generative AI referrals to websites have grown by several thousand percent year on year in sectors like retail, a signal of how quickly behaviour is shifting toward AI mediated discovery (Source: AP News) (Source: Forbes).

For political organisations, that answer layer is becoming as strategic as the evening news once was. If AI models describe you unfairly or omit you entirely, you lose influence even if your ground game and traditional media operation are strong.

From Targeted Ads To Transparent Narratives

In Europe, this shift is colliding with regulation. The EU’s Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising regulation, known as TTPA, entered full application on 10 October 2025, imposing strict transparency rules and tight limits on how political ads can be targeted online (Source: European Commission).

Major platforms have responded by stepping back from political advertising entirely in the EU. Meta and Google have both announced bans on political, electoral and issue ads in the region from October 2025, citing the operational and legal complexity of complying with TTPA (Source: Euronews) (Source: Associated Press). Paid micro targeting is shrinking just as conversational AI becomes a primary source of information.

At the same time, conversational AI is moving into the mainstream. Recent European survey data suggests around 42 percent of adults now use tools like ChatGPT or Gemini at least monthly, with even higher figures in Nordic countries such as Denmark and Finland (Source: Finnish AI Region). In other words, a large share of the electorate is already comfortable asking AI for help understanding complex choices.

How AI Models Build Political Narratives

When a voter asks an AI assistant “Which party aligns with me on housing and small business tax?”, the model does not simply echo slogans. It draws on three layers at once: long term training data from the open web, high authority reference sources such as encyclopedias and official statistics, and real time retrieval from indices and news.

Generative engines then compress this material into a narrative built from attributes: ideology, issue positions, voting record, perceived competence, scandals, endorsements. They favour sources that are clear, consistent and structured, and that appear trustworthy across multiple domains (Source: Butter Marketing). If your own content is thin, vague or missing, the model will still answer the question, but it will lean on opponent framing, old coverage or generic assumptions about your party family.

What Generative Engine Optimization Means For Politics

Generative Engine Optimization, or GEO, is the practice of adapting your digital presence so that generative AI systems describe, compare and recommend you accurately when people ask questions (Source: Wikipedia). In commercial contexts GEO already focuses on how AI summaries talk about brands and products; the same logic now applies to parties, campaigns and advocacy groups.

Unlike classic SEO, which asks how to rank for a keyword, GEO asks how AI will explain you. It is less about where your link appears and more about whether models can retrieve reliable, up to date facts about your policies and track record, then compose them into a fair summary. AI visibility platforms such as RankBee are emerging to monitor how frequently and in what context assistants mention an organisation, and to diagnose which missing signals are holding it back (Source: RankBee).

Making Policies Machine Readable For AI

Most political content is written for persuasion, not for reasoning. Slogans like “strong on the economy” do not map cleanly to the way models store knowledge. To ensure LLMs can reference your policies, you need a layer of explicit, machine readable substance beneath the message.

That starts with how you publish policies. For each priority issue, you should maintain stable issue pages that use plain titles and short sentences stating concrete positions, for example “We support targeted tax relief for SMEs with fewer than 50 employees” rather than abstract claims. Adding structured Q&A sections such as “What is our position on offshore wind?” with concise answers helps AI engines recognise that these are definitive statements of record, not just campaign copy (Source: Butter Marketing).

Technically, you can then express those positions in structured data. Schema.org markup for organisations, people and articles, JSON‑LD blocks that enumerate policies by topic, and FAQPage markup for common questions give generative engines dependable hooks to parse your content. Guidance for businesses already stresses that AI engines prefer clear, structured pages with consistent attributes; political actors can apply the same discipline to policy documents, manifestos and voting summaries (Source: Birdeye).

Finally, models respond strongly to corroboration. Linking out from your policy pages to official legislative records, statistical agencies and reputable media analysis increases the odds that an AI system will see your stance supported across multiple citable domains, not just on your own site.

Measuring And Governing AI Influence

Owning the AI layer means measuring it. Analytics data already shows that referrals from generative AI platforms to websites have grown far faster than traditional organic traffic, and the share of AI referrals relative to organic search has more than doubled within a few quarters for many smaller sites (Source: [Search Engine )). The same techniques can be applied to political content, tracking when AI mentions you, which pages it and which answers send visitors to your properties.

Beyond traffic, you need to monitor narrative quality. Regularly sampling prompts such as ‘Summarise our housing policy’ or ‘What criticism has Party X faced on climate?’ across major assistants, storing the answers, and comparing them to your official record turns vague concerns about bias into concrete misstatements that can be corrected through new content and better citations.

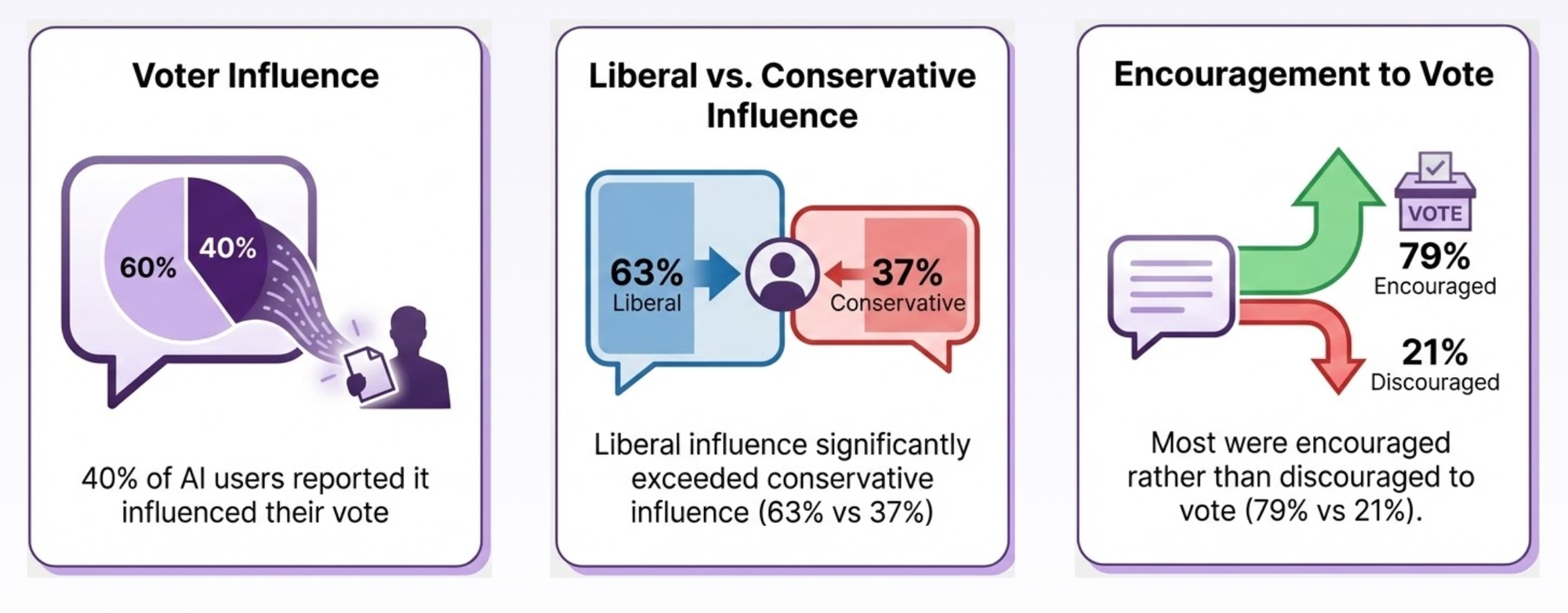

There is also growing empirical evidence that conversational AI can shift opinions. A large 2025 study across 77,000 participants in the United Kingdom found that chatbot conversations about political issues measurably changed people’s views, with the most persuasive AI generated arguments also tending to be the least accurate. For political organisations, that finding cuts both ways: accurate, well sourced AI explanations can support informed choice, while uncorrected distortions can subtly tilt voter perceptions over time.

TTPA already treats paid messaging as something that must be transparent and auditable. The organic AI answer layer deserves the same discipline. That means treating your website, open data, third party citations and AI visibility monitoring as part of a single information architecture, with the same seriousness as your broadcast strategy or field plan.

Owning The Answer Layer

In the coming cycles, visibility will not only be bought through impressions, it will be earned through information engineering. Political organisations that describe themselves in structured, citable ways, monitor how AI systems talk about them and correct inaccuracies quickly will have more than a communications edge. They will help ensure that when voters ask an AI for guidance, democracy is mediated by accurate context rather than silence or distortion.